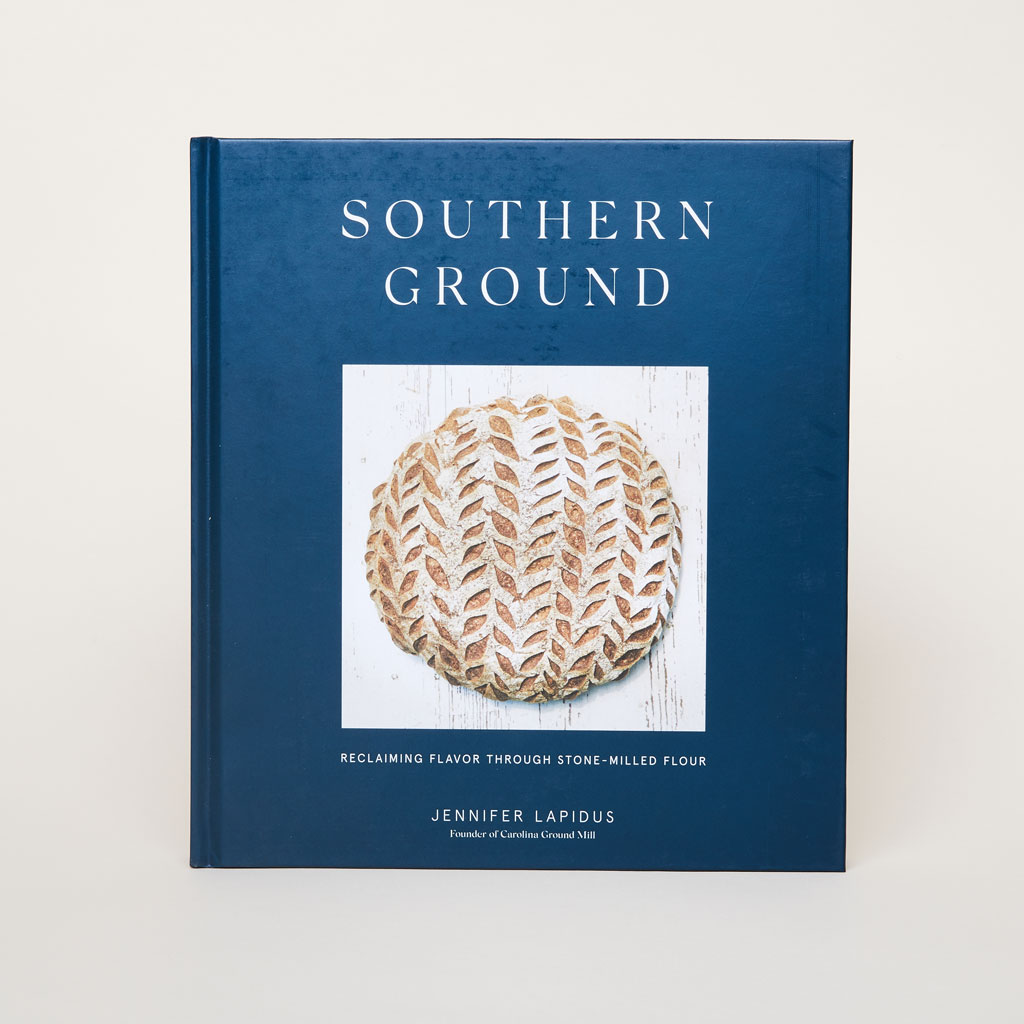

Jennifer Lapidus wrote a book called Southern Ground and I think you need a copy. Obviously, if you’re at all interested in baking breads, tarts, biscuits, crackers, scones and other pastries with 100% cold stone-milled flour, some of which we sell here at East Fork, this is your cookbook. Go right to the source with the baker-turned-miller herself for a collection of more than 80 recipes (like the White Wheat Cake we made and enjoyed immensely) about which Publishers Weekly says, “Ambitious home bakers looking to up their game would do well to pick this up.”

I’d also like to make the argument that this is more than a cookbook. It’s a testament to the early days of modern bakers doing things the one way, stone-milling their own flour and then baking the things they made with it in a wood-fired oven they lit after dinner so they could start baking early the next morning and how these kindred spirits found each other before the Internet came along to do that part of the work for them.

Southern Ground is also a sourcebook about the bakers, millers and farmers who are out there right now, their work and how they got to it. Jennifer is a compelling storyteller, a gifted writer who approached the writing of the book as an opportunity to document her life in bread and fire and grains and along the way, tell the stories of those in the community she knows well and admires, and share many of their favorite recipes, too. Jennifer said, “When we started milling for the bakeries, we knew the bakers would be surprised by the flavor of freshly stone-ground flour. Keeping all the recipes stone ground in the book was a way to tell home bakers that they can fully embrace stone-ground flour and have really interesting cakes and breads and cookies. It’s so flavorful and interesting.” She also noted that North Carolina grows the most grain for pastry flour in the South.

From the Analog World to Now

Photo courtesy of Rinne Allen

I asked Jennifer what it feels like today, a time when baking is such a visible profession and the regional grains movement, which she helped start, has great momentum. She said, “It’s amazing to especially place it in today’s context. I’m sitting in my office and I feel like I’m in the driver’s seat, receiving wholesale applications from bakeries throughout the southeast who use natural leavening (sourdough) and are seeking stone-milled flour and I’m like, this is catching on. I started my bakery in the early 90’s. There were so few of us in the whole country doing this, and there was no social media or world-wide web for that matter. I was a wood-fired oven baker in Madison County and a single mother. My daughter and I would eat dinner and then after dinner, we would go out and set the fire. At four in the morning, I would start working in the bakery and by seven, rake the coals to the front of my oven, and then get my daughter ready for school. I was living this whole private life. These days, it’s very public. On the Internet, there are all these bakers, and they have millions of followers, who watch them shaping their bread and they have music in the background. No judgment, but it’s just this whole other thing. In my life these days, I have a lot of plates spinning. I think back to those private spaces, just watching the fire in the oven. It was just so magical.”

I also wanted to go back a bit farther, even before she opened Natural Bridge Bakery, Western North Carolina’s first wood-fired bakery in 1994, a time when, after traveling to Arkansas from Georgia to attend the annual meeting of the Cooperative Whole Grain Educational Association, and striking up a correspondence (yes, with stationery and postage stamps) with Alan Scott, whom she describes in Southern Ground as “a mythic figure who was baking naturally leavened whole-grain breads for his community in a wood-fired brick oven he’d built in his backyard.” Alan also built brick ovens for many people over the years.

Jennifer said, “When I apprenticed with Alan Scott, it was a whole other world. It was Marin County, California, in an era when so much of this stuff was just becoming. He was a fringe thinker. We’d have lunch with Alice Waters because he repaired her oven; we did a hands-on demonstration at the George Lucas studios because he built an oven there, and we’re telling these highly trained chefs there about the beauty of whole grains and natural leavening. We were just so passionate and excited. Culinary schools were not teaching anything about natural leavening, let alone whole grain baking. And again, at the time it was a very analog world.

“What I think is exciting is to see how far we’ve come, how it has really taken off and gotten momentum. Just within the time of this mill getting started, I’ve seen so much change and food awareness and the regional grains movement. If you’re a chef or a baker and you’re not engaged with your regional mill, it says something about the type of baker or the type of chef you are, I think. I think that Dan Barber has done a lot to give voice to some of this stuff, for sure, in terms of the value not just in heritage but of public [grain] breeding and modern varieties that are regionally adapted, not GMO, but also in looking at institutions we can claim for our own that in the past had been usurped by industrial agribusiness . That was a big surprise to me that I could engage with the USDA and have them actually work with me. I never expected to be seen in that world as someone with a voice and the idea of bringing together bakers for the project that became the mill. Initially we were just a handful of bakers in the western part of the state.

From Baker to Miller and Writer

Photo courtesy of Rinne Allen

Photo courtesy of Rinne Allen

I asked Jennifer how she met people in the region who were interested in, and baking with ingredients and methods similar to hers. This conversation about community led to how, some years later, she found herself becoming a miller.

Jennifer said, “With the Asheville Bread Festival, Steve Bardwell had this idea of bringing us together (I’m now one of the organizers of the festival). I had managed the farmers’ market where I sold bread and it was so rewarding. I was doing something that was good for all of us. As a collective, we come together and we grow together.

“The mill became a thing because we brought so many bakers together and created a market for growers in Carolina and I was able to say, ‘Look, your grain is special, not just because it’s certified organic but because it’s grown here in the South, in North Carolina. You don’t have to be competing in this huge market; you can be geographically distinctive and we will market you that way,’ but I couldn’t do that as a single bakery, really, to make an impact.”

She also talked about when in 2008 the economic crisis resulted in an increase in the price of wheat by as much as 130%. She said, “2008 was the moment when a door or window opened, when we knew that the system didn’t work because with the price of wheat going up 130%, a baker cannot [deal with that] as margins are too small. “

2008 also marks the year that Jennifer enrolled in the MFA creative nonfiction writing program at Goucher College. Being asked to write an essay for a book by Peter Reinhart sparked her interest in telling the stories that always intrigued her about craft bakers who felt driven to do things like bake in a wood-fired oven before anyone else doing it, and that of course includes her own story, and the story of the mill.

More Than Milling

Photo courtesy of Rinne Allen

2008 is also when Jennifer began to talk with farmers in the region, not to buy their harvests, which at the time were mostly feed-grade wheat crops, but to convince them to grow wheat to be milled for flour and to sell it to her. She spoke about building those relationships. These are some of the stories she tells in Southern Ground, all parts of the larger narrative truly compelling, just like the argument she makes for bakers to use regionally-sourced stone-milled flours. She adds, “We could take local grains and use an industrial roller mill and you would never know it’s local. So reclaiming the stone mill to produce flavor-forward stone-ground flour is part of this, too.”

In the coming months, Carolina Ground will move to a larger facility in Hendersonville, a town about 20 miles south of Asheville. There will be space for not just the mill but also, a retail shop, a test kitchen and on-site, longer-term storage and with that, Jennifer’s hope to buy other rotation crops like beans from the farmers she works with. She said, “Engaging on a deeper level with growers regarding rotation crops will help us, too, so we don’t have a whole year when we aren’t buying anything from them if their grain crop does not make the grade.” As for equipment, she said, “We have a mill and a sifter and we’ve moved to a pneumatic system but we’re still working with eight gallon buckets now. We’ll be setting up in a way that’s more efficient, less dust, not as hard on the back.”

Jennifer also spoke about something less tangible but nevertheless crucial that the new facility has inspired her to think deeply about: balance. She said, “Most people, if they were going to invest in equipment, would want to grow their business. But I have no interest in getting big. I don’t think it’s wrong to want to do regional milling on a large scale but I also don’t think it’s wrong to figure out how small we can be and still be sustainable and balanced, finding what really works for us and for the space and the fabric of the business, just being intentional. We want to produce more efficiently so that our workers can have a more diversified experience of working at the mill, so they’re not just clocking in and milling all day, and that’s all they do. We’re going to have gardens and a retail aspect. East Fork has inspired me in this way, it’s so important to focus on the experience of work.

“One of my favorite quotes is ‘industry without art is brutality’ and that came out as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution. How do we balance out the manufacturing? There is a draw for something inspiring. Milling is good work and it’s important work and there is definitely a craft and an artform to milling but when you get into an industry where it’s ‘we need to make 2,000 pounds of this product,’ there just needs to be a balance.”

She mentions the sign-off from the story-centered podcast The Moth: have a story-worthy week and said, “Currently we don’t have story-worthy weeks. We have 12 hour days and we come home exhausted, but we are adding some much needed mechanization. So the building is an opportunity to realize a greater vision of this mill. Home bakers are using our flour, professional bakers are using our flour, farmers are calling me, we have long-standing relationships. We have the foundation. But I want a story-worthy week, so I’m excited for this next chapter.”

Buy Southern Ground by Jennifer Lapidus