An Interview with Madison County Basket Weaver, Louise Langsner

In the mid 1970s, after months of living and working with farmers and craftspeople in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, Louise Langsner and her husband, Drew, came back to the States, packed up their van and went out in search of their own path around the capitalist hustle. For 35 years they’ve run Country Workshop, an internationally recognized woodworking school with a focus on handwork with hand tools, in a tucked away holler deep in Madison County, North Carolina.

Louise makes baskets with willow that she’s grown, harvested, and prepared on her land. On an icy day this winter, Louise and I sat down in the home she and Drew built to talk about the life they'd built by hand. Read on to find out how two young Californians left it all behind and went back-to-the-land way before it was cool. It's a beautiful story.

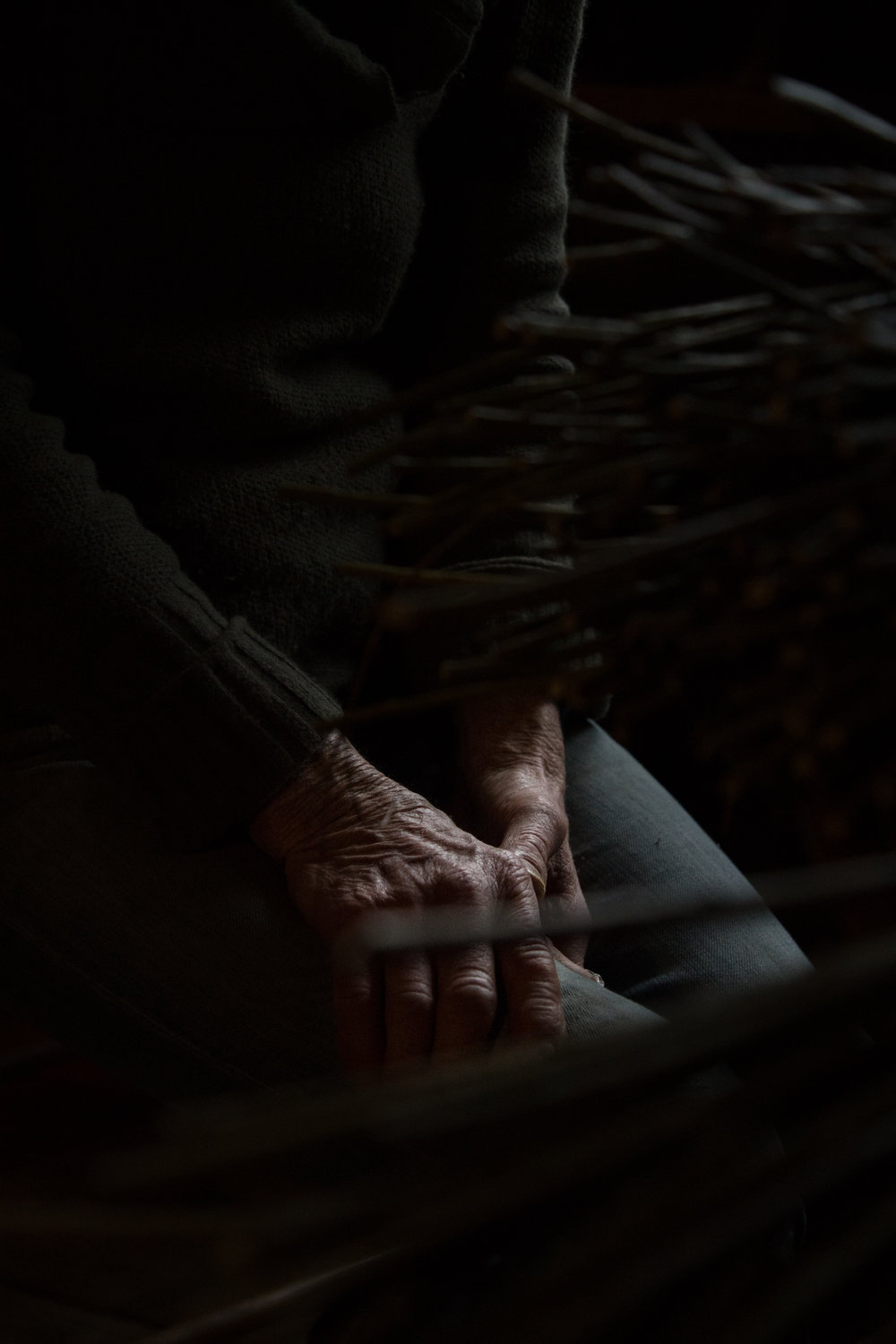

Madison County basket weaver Louise Langsner, using a Native American technique for splitting dried willow.

Connie: I want to start from the very beginning and hear about what brought you and Drew to this place and this life. Can you trace an arc that landed you here? Or does it feel like life just all happened out that way?

Louise: Well, Drew and I got married in 1971. Drew had already planned a trip to Nepal. He had this overland trip from Europe to Nepal in mind, and so I got on board. We thought we were gonna take planes and buses and hitchhike and the reality of that didn’t work for us. So we got a motorcycle instead and got going.

C: Where did you start from?

L: We flew to London, and then we got the motorcycle in Germany. It was a really rainy winter so we dried out in Greece for the season and took a ferry over to Turkey. Between Germany and Greece we were in Yugoslavia and Southern Germany. We stayed with farmers and peasants. Well, we never got to Nepal! The motorcycle wasn’t ever going to make it all the way. At the edge of Turkey there was a little sign pointing to Iraq - just a little wooden sign with an arrow. And it was just obvious that the motorcycle had had enough. And so we turned around and went back through Turkey and we ended up putting the motorcycle on a train and taking it back to Germany. We traded it in for a little VW Bug - much more reliable! So we started driving all around Switzerland and we picked up a hitchhiker who let us stay at his place in the Alps. That was when we first learned about coopering. We saw these beautiful wooden milking buckets and Drew got the idea that he really wanted to learn to make them. We did some other traveling and we lived around Scandinavia, but made our way back and stayed with the cooper. Drew did a three month apprenticeship and I stayed with another friend up in the mountains who was a cheesemaker. That kind of inoculated us. We liked being with people that made things - made their own food and raised their own food and lived in home that they’d made that were full of more things they’d made.

C: Had you been exposed to much of that before this trip or was this kinda like a revelation?

L: It was an absolute revelation. The closest I think I’d been to that was staying in West Virginia in the late 60’s and seeing people that lived that way - subsistence farmers basically. But you know, in this country we see that sort of life as poor.

C: Something that they weren’t doing by choice?

L: Well, it was sort of by choice but sort of not. Because of the complicated coal mining impact on their culture. But the people that we stayed with on our travels felt rich. Their lives felt rich. Even though they were, you know, financially poor. They had really good, beautiful things in their life.

C: Good food, beautiful land, and...

L: ...and they were happy. They had their families and they all just felt connected - and that felt important to us. When we got back here, Drew had a contract to write a book. So we wrote this book, I helped some, called Handmade about that traveling time.

C: Drew had the contract before you set off on your trip?

L: Yeah. It was a fortunate accident sort of thing. We had a little money to help with the trip from that and then we made the book and after that we really wanted to find some land. A lot of the Back to the Land type things were going on then and that’s what we wanted to do, but we were out of money. A friend had already bought this place. He had been looking around the Southern Appalachians and bought 200 acres, this cove we’re in now, with the idea that it would be a craft community or an art community of some kind. Drew wanted to have wood to work with.

C: He’d been working with wood before he went on the trip?

L: Not in the same way, not handwork. He and a friend had been making children’s playgrounds. He went to art school for sculpture and painting, and he liked making things. So that was their business. His friend stayed with that business and did that for a lot of years. Kind of morphed into adventure playgrounds - you know - with big wood sculptures. So yeah, he always liked making things and working with his hands, but it was really the Cooper that introduced him to hand tools. Anyway, we moved here without a plan. The friend said we could come here and if we liked it we could stay or if we didn’t we could look around and find something else. We stayed. Our friend never even came. He ended up staying in California.

C: That’s where you’re both from, right? California?

L: We both are, yes. Although I grew up near Chicago and then went back. Drew was born and raised in Los Angeles.

C: That’s what I thought. And his father was from there too?

L: Both parents. I think that his grandparents moved there from New Jersey. They had been on an utopian commune in New Jersey and then moved to Ontario and had a health farm. And then they moved to Los Angeles. Drew had really been done with Southern California a long time ago. He’d been living up in the Bay Area for ten or twelve years. Anyway, we had a 52’ Chevy van and Drew made it into a little camper inside and we had a trailer and we drove that thing all across the country and then straight up this muddy driveway. And we stayed in what’s now Naomi’s cabin [Naomi is Drew + Louise’s lovely daughter]. It was built in the late 20’s and it was basically a shack. But we were just happy to be here. So, Drew started making wooden things like pitchforks and started selling them to a little country store in Kentucky that sold things like that. And we both kept writing magazine articles. People found out about us and contacted us through the book, Handmade. We made so many wonderful friends through that. Because there was no Internet people really had to want to find us - and somehow they did.

C: How did they find you?

L: I’m not even sure! I think they wrote to the publisher! Can you imagine? But people just started showing up and saying, “We read your book!” We met really, really good, lifelong friends that way. [Guys, Drew and Louise live in the middle of nowhere. The Internet has made us so lazy!] We kept writing articles about homesteading and gardening for things like Country Journal and Mother Earth News and Organic Gardening, so people kept hearing about us. And one of the people that contacted us from the book was Bill Coperthwaite who had the Yurt Foundation up in Maine. And he came down and met us. The hand woodworking counter culture community was pretty small. But he was a person that liked to travel and liked to make connections and introduce people and always learn about new crafts and things like that. He came down and visited us and brought a man he knew from Sweden, Wille Sundqvist [check out the video embedded here showing Wille at work]. Billy knew just a little English, but he was a fabulous craftsperson. He showed Drew some things like knife work and axe work. We had the idea that it would be wonderful to learn from him. And since we couldn't afford to go back there, we invited him to come here. So then we thought well, we’ll see if he would come to teach a class. He agreed and the next year he came back and taught a couple classes for us. We put some announcements in some of the magazines we wrote for and people came. We had no running water, no electricity and and no workshop - the classes were in the cow barn and people camped. They loved it. Billy is an incredible teacher. He was what they called a craft consultant in Sweden and he grew up with the craft tradition. He is now 90 and has been making things with wood since he was big enough to hold a knife, so about 85 year - a truly wonderful person and teacher. Everybody just loved him. The second class we had that summer was with Peter Gott who lived down the road. He was a superb builder of log homes and he agreed to teach a class. So I think that was another two weeks of classes. And that was the beginning of Country Workshops. We didn’t come here with the plan that we were gonna have a school - it just happened. And we kept doing it, adding classes, meeting more people and inviting them to come teach. It grew from there until one day we looked around and said, “Oh, we’re running a school.”

C: When was this all getting started?

L: The first class was in 1978. That’s when the first logs for this house we’re sitting in now were hewed. And then Drew worked on it for a couple more years and we moved in in 80’.

C: It’s amazing that people found you way out here without Internet. Though then things were so much less saturated. There was so much less noise. Now anybody can teach a class and put it online. Even in Asheville there’s just so much noise that it’s so hard to sift through and find out what’s real and worth your time.

L: There were hardly any places to go for that sort of thing at that time. Even John C. Campbell and Penland were all but dead until they were revived over the years.

C: Both of them had a lull in popularity?

L: Yeah, I think probably during the 60’s maybe even the 50’s, the interest in handcraft was pretty low. No one was thinking, “I think I’d like to learn how to weave.”

C: Right, they were like, “That stuff’s for grandmas. I’m over it.”

L: Right. But slowly people realized that sorta thing is really enjoyable and important.

C : In the last few years of teaching classes did you see a difference in who was coming out for classes?

L: It was always pretty much retired guys and mostly men. Gradually more women started coming and also by the last five years we were getting younger people and more mixture of ages. I think there are a lot of reasons, but I think a lot of people now work so much with computers or in their head and so doing something with their hands is really appealing.

C: We grapple with this a lot because most young people who are able to take on traditional apprenticeships like that come from relative privilege and can be financially supported by their families. It limits who is able to come and work.

L: The model is really hard to make work in our culture. Like the cooper that Drew apprenticed with - growing up his family was so poor that he had to be sent to another farm when he was 7 years old to go to work. He worked on the farm and sent money home until he was a teenager and then he apprenticed with a cooper. At that time the cooper worked during the winter and did farm work during the summer. His apprenticeship was seven years long and only then did he feel like he was ready. And still he was only beginning to make money as a cooper in 72’ when we met him. City people who had some money started to realize how special his work was. He kept knocking out rougher buckets for farmers and feeding buckets but he also made really beautiful decorative ones. I remember him telling Drew you know, “I’m sorry, I can't pay you, but I’ll teach you” so they didn't pay their apprentices anything.

C: That’s how it is in so many apprenticeship traditions. But it’s so hard to make that work in our capitalist culture. Taking that tradition and trying to grid it onto our system now is so difficult. Anyway, let’s talk baskets. Did you teach basket weaving in classes at all?

L: I did. When we first moved here I started making White Oak baskets and I taught some classes in that, but it’s so hard to find good trees. Then I learned about growing and harvesting willow, so I made the switch. Most of my teaching, though, was with one or two people at a time - that’s what I like. I never really taught during the Country Workshops because I was too busy cooking all the meals and taking care of everyone’s needs.

C: Is there anyone in this country who are making willow baskets on a productions scale?

L: In this country, no, I don’t think so. In Iowa there used to be a colony who had it as part of their business and I think there was also one in Ohio, but no longer. There was a time in Madison County when the Presbyterian Church had a mission here and one of the things they set up was a craft outlet. So people in the county would give them designs or tell them what they needed and they would weave baskets and then the church would find ways to sell them.

The beautiful, strong, working hands of basket maker and homesteader, Louise Langsner

C: Did you learn from someone in Madison County?

L: No when I got interested in it I only knew of one person at that time, it was Bonnie Gale up in New York. I started growing willow before I had any idea how to use it.

C: You started growing it before you started making baskets? Wow. You never were just buying willow?

L: No at that time I didn’t know of a source for willow. A friend from California brought me a little plant to show me. You propagate it by you get little cuttings and you stick them in the ground and they grow.

C: Is it pretty quick growing?

L: Yeah. In a few years you’ll have quite a few rods from each one. Portuguese and Italian grape growers that started in California used to tie their grape vines up with willow - he brought me some of that. He was somebody that we had met from reading Handmade. He had studied gardening with Alan Chadwick in Santa Cruz and came out to meet us. At that time all of us were just interested in anything that you could grow and use. So I started growing it and then I tried to start teaching myself from books, but I just couldn’t do it on my own. A friend who had moved to Portland found a teacher out there, Margaret Mathewson, and she was offering a class so I went. What I learned from her got me going, but I could have used a lot more teaching. I still had to teach myself how all the different materials behaved - using round willow is so different than using flat materials, which is what I’d learned with. With willow, every move counts. If you get a kink in the willow you really can’t undo it. It’s a fussy material.

C: Could you walk me really quickly through the process of growing willow?

L: When you want to start your willows you get some cuttings from somebody else. It likes to grow without weeds so you need to prepare your land. And then you stick it into the ground. You’ll take a nine inch piece and just leave two buds sticking out of the ground. Willow bark has a hormone for rooting, so it’s suited for it. The first year you’ll get a few little shoots. At the end of the growing season during the winter, that’s when it’s cut off. Some growers leave a little stump, but it can be done either way. So the willow grows for a season and then once the leaves fall and the plant is dormant you cut it. The rods that are left is what’s used for weaving. I take all those rods and sort them by length and then dry them for at least a year. When I want to weave with them I have to soak them. Because I weave with the bark on so the soaking time is roughly a day per foot of rod.

C: Is leaving the bark on an aesthetic choice?

L: Yes, I love the different colors of the bark - there’s so much variety. I look for varieties that grow send out thinner shoots, because the bigger varieties get too big here with the clay soil and all the good rain. If the willow grows too well I have nothing to weave. But I like to collect all the different varieties just for fun, even if they aren’t the best for weaving.

C: I heard from Rob and Karie that you’re maybe making some baskets for the new Echoview storefront.

L: Yes. And it’s giving me an opportunity to try some different shapes. Rob is interested in a basket that’s not symmetrical. It’s nice that they already have a use in mind already. There’s many basketmakers out there that are technically very good, but they are also very artistic and they’ve been exploring that kind of shape. Where as I’m much more stuck on functional straight-forward things. So this has been a fun challenge for me.

A willow basket in use, woven by hand with willow grown by the maker in Madison County, North Carolina.